Harbin

Hot Springs’ Actual/Virtual Ethnography

Naked Harbin Ethnography & Coming of Age in

Second Life

Chapter

Titles, Summaries and Table of Contents

"Naked Harbin

Ethnography:

Hippies,

Warm Pools, Counterculture, Clothing-Optional and Virtual Harbin"

Academic Press at World University and School (2016)

Part I: Setting the Harbin Hot Springs Stage

In chapter 1, titled 'The Subject and Scope of this

Inquiry,' I begin by engaging the work of anthropologists Bronislaw Malinowski

and Tom Boellstorff by focusing on arrivals to and departures from Harbin Hot

Springs, as well as everyday life. I next lay out some terms of discussion,

followed by a brief anthropological history of the emergence of actual Harbin

and then virtual Harbin. Next, I characterize Harbin residents, the 150-180

people who live at and near the Harbin property, before describing what this

book does.

In chapter 2, titled 'History,' I examine some prehistories

of Harbin, contextualizing Harbin as a countercultural vision emerging out of

modernity. I then characterize some histories of Harbin followed by a personal

Harbin history. After examining some histories of Harbin research, including

some of the challenges of developing a virtual Harbin and writing this Harbin ethnography,

I explore Harbin's history as a kind of actualized vision, ethnographically.

Lastly I characterize how virtual Harbin emerges out of the 'actual.'

In chapter 3, titled 'Method,' I examine Harbin on its own

terms, engaging an important anthropological, textual tradition. I then

characterize participant observation, particularly in terms of interviews,

fieldwork, and virtual developments, before examining ethics, some anthropological

claims, and the significance of reflexivity. Lastly, I characterize

methodologies for comparing and contrasting actual Harbin and virtual Harbin.

Part II: An Ethnography of Harbin as Counterculture Emerging

from Modernity

In chapter 4, titled 'Place and Time,' I examine

ethnographically the significance of geographical place – the Harbin valley,

its waters, and northern California – in terms of sociocultural processes

there. I characterize, too, the unique buildings such as the Harbin Domes, the

Conference Center, and the Harbin Temple. I then examine the significance of

traveling to and from Harbin. Lastly I explore questions of immersion in the

waters as well as 'oneness,' 'now,' and 'presence' at Harbin, due to the waters

and the hippie New Age ways of thinking, along with the sense of timeliness

there.

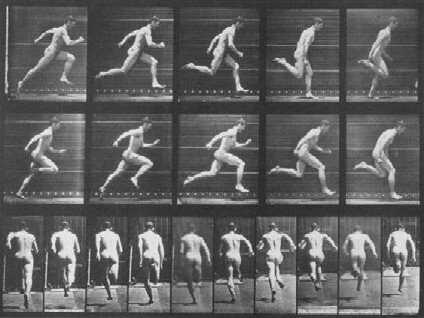

In chapter 5, titled 'Personhood,' I characterize aspects of

personhood and 'Self' at Harbin. I then examine Harbin's life course in the

context of its pools, the 1960s, Heart Consciousness Church and counterculture,

and the significance of Harbin's clothing-optionality. In this chapter, I also

address questions of gender and race at Harbin, before examining ways to

contextualize questions of agency, particularly in relation to hippies and the

1960s.

In chapter 6, titled 'Practices and Beliefs,' I examine issues

related to Harbin language, especially New Age, astrology, friendship, long-time

residents, intimacy and cuddling in the pools, sexuality, and Harbin's

openness, love, connectedness, and oneness, vis-à-vis what has emerged at

Harbin in the 40 years since the early 1970s.

In chapter 7, titled 'Community,' I examine issues related

to Harbin residents as 'tribe' or family. I then examine ways in which

workshops and events at Harbin have led to fascinating 'New Age' explorations,

before investigating the role that Heart Consciousness Church and New Age

Church of Being have played in terms of 'Heart Consciousness' and its

expressions at Harbin. Lastly, I examine the significance of Harbin's pool

area, along with the ways in which this has informed and generated a kind of

milieu of openness through the decades. Harbin in some curious ways remains a

kind of hippie, almost-spiritual, New Age center in northern California.

In chapter 8, titled 'Political Economy,' I examine ways in

which Harbin as a business, emerging out of 1960s and early '70s

'counterculture,' co-informs Harbin along with Heart Consciousness Church, making

Harbin sustainable. I contextualize this aspect of Harbin within Lake County

and Northern California, both when it began and today. After investigating the

significance of some of the roles that money and labor have played at Harbin, I

look at questions of property, Harbin governance, and elements of inequality,

in terms of life in the Harbin valley.

Part III: Virtual Harbin

In chapter 9, titled 'The Making of Harbin Hot Springs as

Ethnographic Field Site,' I explore how to create virtual Harbin in a virtual

world environment like Second Life. I also describe ways I have engaged the

actual Harbin family to help with the building of this, as well as its

maintenance and its culture. Finally, I characterize how I, and others, invite

and encourage avatars to visit virtual Harbin to build community.

Scott MacLeod

Summer 2015

Coming of Age in Second Life:

Table of

Contents

Summary of Boellstorff (2008), Coming of Age in Second Life

JULY 13, 2009

tags: anthropology, cyberanthropology, epistemology,

ethnography, ICT studies, internet studies, local politics, media anthropology,

media ethnography, media theory, new media, practice theory, Second Life,

sociality, technology

j8647

Boellstorff, T. 2008. Coming of Age in Second Life: An

Anthropologist Explores the Virtually Human. Princeton: Princeton University

Press.

NB – See previous blog entries for more detailed notes on

each chapter

PART I: SETTING THE VIRTUAL STAGE

Chapter 1. The Subject and Scope of this Inquiry, 3-31

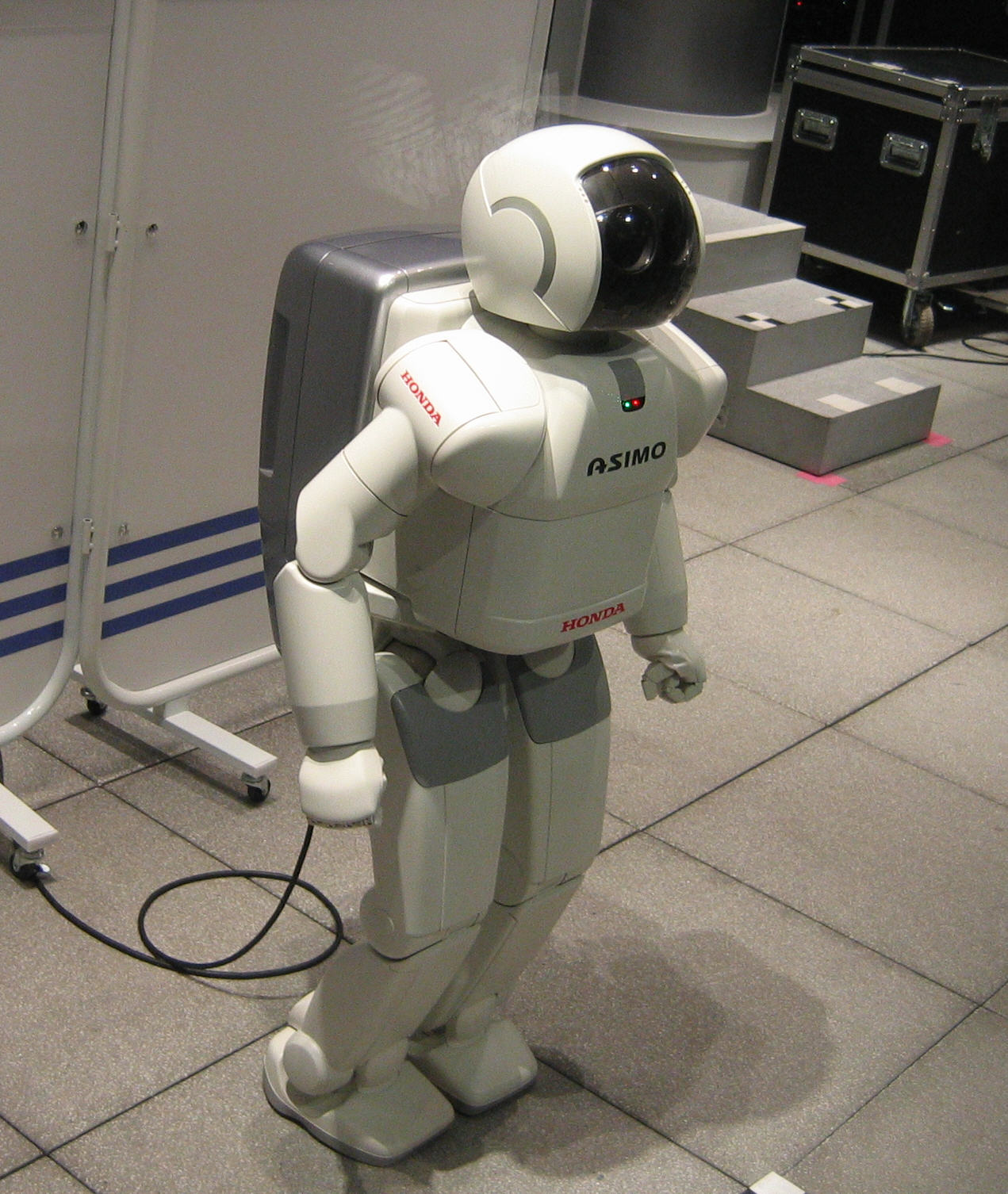

The book is an ethnography of the virtual world Second Life

(SL) from June 2004 to January 2007. The aim is to rehabilitate the notion of

‘virtual’ by studying virtual worlds in their own terms. Inquiry into both the

historical continuities and changes of this virtual world. The author argues

that the notion of posthuman is misleading, for it is in being virtual that we

are human. Instead he sets out to investigate virtual worlds as ‘techne’ (human

practice that engages with the world and creates a new world as well as a new

person: homo cyber). Second Life is most certainly not a game for its

residents, and we must take residential sociality seriously. Anthropology can

make a contribution to the study of emerging forms of cybersociality.

Chapter 2. History [of Virtual Worlds], pp. 32-59

The crucial historical breakthrough with virtual worlds came

in the 1970s with Krueger’s invention of the first, rudimentary virtual world

which allowed two people to interact virtually in a ‘third place’. This was a

fundamental break from existing forms of telecommunication in which two places

(A and B) are remotely connected but without a third place. Another precursor

to Second Life was first-person perspective of videogames from 1970s onwards.

What is new about virtual worlds like Second Life is that techne now resides

inside this virtual third place, that is, SL residents craft the very objects

of their inworld practices.

Chapter 3. Method, pp. 60-86

The starting point of project was methodological: What can

ethnography tell us about virtual worlds? Undertook almost whole study inside

SL, as avatar Tom Bukowski. Takes issue with previous Internet ethnographies

(eg. Miller and Slater 2000) for insisting on embedding online worlds in actual

worlds. Argues that you cannot explain inworld sociality via actual-world

sociality – must understand it in own terms as it is no recreation or

simulation. Human selfhoods and communities are being remade in SL. Opts for

holistic approach to SL as he did in previous study of Indonesia – overarching

cultural logic is the focus, not subcultures. Adapting Geertz, he sees the

cultures of virtual worlds as being ‘highly particular’. Participant

observation is form of techne: the ethnographer crafts events as they unfold.

This mode of inquiry also shows that we must pay more heed to the mundane in

virtual worlds and less to the sensational.

PART II: CULTURE IN A VIRTUAL WORLD

Chapter 4. Place and Time, pp. 89-117

There is a long tradition in mass media studies in which

virtual worlds seen as antithesis of place-making. Yet virtual worlds are ‘new

kinds of places’; they are ‘sets of locations’. SL residents have strong sense

of place, e.g. when talking about their SL homes: “It’s my place: it’s mine”.

One key feature is 3D visuality, unlike blogs or websites. Although commodity

economy predominates (both persons and things are commodities), it’s not all

neolib consumerism: there is also barter, communal ownership, donations, etc.

That said, ownership is important dimension of SL sociality, non-owners are

socially impaired. Another key aspect of sociality is synchronic interaction

which makes virtual worlds feel like worlds, but this always threatened by

‘lag’ (delayed action) and ‘afk’ (absent from keyboard). Although person and

avatar reunited after afk, users are never completely ‘back’ as physical body

always remains away from virtual world.

In contrast to virtual reality, here what matters is social not sensory

immersion.

Chapter 5. Personhood, pp. 118-150

Aim of chapter is to investigate ‘everyday senses of virtual

personhood’ in SL. Re: life course (Giddens), what is SL course? Many residents

had more than one account so actual and SL selves not necessarily coterminous.

However, time constraints in having several avatars – time resists

virtualisation far better than space. Unlike game worlds, no skill levels here,

although newbies easily recognisable for lack of practical skills. Changes in

actual life could impact on SL, e.g. family member falling ill. Leaving SL could be painful, ‘charted on

blogs and commemorated with farewell parties’. SL embodiment not a simulation

of real life: residents experienced ‘corporeal immediacy’. Contrast between

Haraway’s cyborg corporeality (prosthetic continuity human-machine) and that of

SL’s homo cyber (actual-virtual gap). Race also played a part, but often

tacitly: default avatar race was white.

Chapter 6. Intimacy, pp. 151-178

SL brought about new forms of online intimacy, not just

reflection of actual world. Text was ubiquitous, favouring deaf people but

excluding the blind. Code-switching across textual modalities was common, e.g.

IM and chat in relation to topic and its intimacy aspects. Frienship not sex is

‘foundation of cybersociality’ in SL. Most visible sex subculture was BDSM.

Friendship is all about choice and egalitarianism. Residents felt you could

know people in SL ‘from inside out’; residents wore their souls (opposite to

actual life). SL accelerates friendships and love. As is typical of C20 love in

general, SL love tied to place and belonging. Trust could be internal to SL,

but some newbies didn’t get this, saw people as being far apart rather than

‘copresent in a virtual place’. Virtual kinship also to be found; many child

avatars, their child play a subset of ‘kin play’. Such a hypersocial place as

SL generated widespread emic concerns about addiction not so much to building

or scripting but to socialising. These folk anxieties suggest fear of

‘compromised agency’ of homo cyber who is supposed to be autonomous, creative,

etc.

Chapter 7. Community, pp. 179-201

Virtual worlds are

places, sites of culture where people interact. After a period of time, they

become communities. Linden Lab, however, can use the vague rhetoric of

community for its own goals. For SL residents social places are paramount.

Avatars can be represented as dots on the screen – these dots tend to beget

more dots. SL events are manifold highly varied and take place in real time,

they are ‘a conjunction of place, time and sociality’. Kindness and altruism

are very common in SL; some official recognition/rewards for such behaviour

from Linden Lab but not too significant.

As Manchester School taught us, though, conflict is integral to all

human endeavour. Serious forms of inworld harassment included lag bombs,

physical assault, etc. The old CMC issue of disinhibition present here as well,

though inhibitions not so much obliterated as redefined. Griefers

(troublemakers) not acting in a moral vaccuum, their griefing in fact is

bedrock of own forms of sociality and community. In response to griefing and

Linden’s laissez faire approach to governance, a manner of ‘frontier ethic’

arose among some residents. This chapter also considers the issue of interworld

travel, migration and even virtual diasporas seeking refuge in SL from extinct

virtual worlds. Finally, actual-world meetings of SL residents took place but

exaggerating their importance reveals common assumption that cybersociality not

meaningful in its own right.

PART III: THE AGE OF TECHNE

Chapter 8. Political Economy, pp. 205-236

Economy: SL shaped by Californian Ideology, ‘bizarre fusion’

of Frisco bohemia and Silicon Valley technopreneurialism. SL good example of

‘creationist capitalism’ = labour as creativity, production as creation, so

that consumers labour for free. The motto, embraced by many residents, is “Be

Creative”; selfhood becomes ‘the customisation of the social’. SL part of

internet-wide ‘pronominal logic of customisation’, e.g. MySpace, MyYahoo. Many residents

find SL creative practice to be inherently rewarding. Although time and place

main foundations of SL, money sensationalised, esp. ability to make ‘real

money’ (US$). Linden went from SL as object- to property-based economy. To

build something permanent must own property: again, virtual worlds are places.

By contrast to other forms of digital reproduction, there is virtual

materiality inside SL, e.g. avatars can actually sit on a chair. Social

inequality took on many forms. Governance: Unlike actual worlds, virtual worlds

can be owned, usu. by a corporation. This gives corp unprecedented influence

over residents. Total surveillance, no privacy for avatars, users always aware

of this. Authoritarian, top-down governance but some attempts at devolution to

residents. Some resistance in evidence, e.g. demo to bring back credit cards

checks on new residents, concerns about safety of avatar and property. In sum,

complex governance dialectic binding Linden and residents.

Chapter 9. The Virtual, pp. 237-249

In this final chapter, the author sums up the argument and

explains what SL is and what it is not. SL is not a simulation; it may

approximate aspects of reality for purposes of immersion, but it does not seek

to replicate the actual world. SL is not a social network comparable to

Facebook or MySpace – it is a place. SL is not a posthuman world; in fact, it

makes us more human. SL is not a sensational new world of virtual

Californication, virtual money that can be exchanged for real money, etc; more

often than not it is place where everyday banal forms of interaction take

place. SL does not herald the advent of

a Virtual Age that will sweep aside the actual but an Age of Techne with

continuities as well as changes with what came before. Humans have always crafted

themselves through culture (homo faber). What is truly unique about SL and

other virtual worlds is that they allow the emergence of homo cybers, humans

who can craft and recraft new worlds of sociality in a virtual ‘third place’.

In SL you can find friends and lovers, attend weddings, buy and sell property:

you cannot do that inside a TV programme or a novel. This is why an

ethnographic and holistic approach has worked well, because virtual worlds are

‘robust locations for culture’, locations that are bounded but at the same time

porous. The book ends as it started: with a reference to Malinowski’s

pioneering ethnographic work.

...

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.